Toward the end of the year, a draft law on the regulation of investment funds was submitted to Parliament. Of particular interest is the fact that the draft introduces a relatively new type of investment vehicle for Kazakhstan – private equity funds. Private equity funds pool capital to invest in the unlisted equity of portfolio companies and typically commit it for extended periods. Beyond financing, they bring hands-on management expertise.

In Western markets, private equity funds function as global macro-investors. By way of illustration, The Carlyle Group manages approximately USD 426 billion in assets, while its competitor, Blackstone, reports assets under management exceeding USD 1 trillion. Firms of this scale often command resources exceeding the GDP of some countries, such as Kazakhstan.

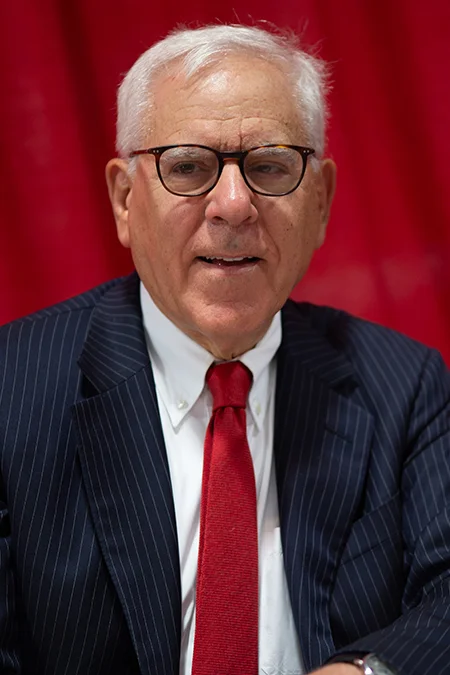

David Rubenstein – Co-Founder, The Carlyle Group

Against this backdrop, the question naturally arises: why has Kazakhstan’s mega-regulator chosen this moment to create a regulatory framework for private equity investors within the mainland jurisdiction? Traditionally, private equity funds are incorporated in offshore financial centers. The Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) already offers a platform for the incorporation of private equity funds. Yet, according to AIFC Governor Renat Bekturov, speaking at the most recent Astana Finance Days conference, private equity is still area to develop. The Government’s rationale, as outlined in the Prime Minister’s explanatory note to the Parliament members, is straightforward. The central bet is on accelerating economic growth through both domestic and foreign investment. This implies a shift away from government-financed megaprojects toward projects funded by private capital. The open question, however, is whether the Government already has specific investors in mind – or whether this initiative is aimed at an as-yet undefined future.

Blackstone Chairman and CEO Stephen Schwarzman with Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, United States, 2025

Private equity funds are attractive to both investors and the business community for several reasons.

First, they represent an alternative source of capital for the economy, reducing reliance on bank lending. This is particularly relevant at a time when profit growth in the banking sector is slowing. Moreover, the long-term implications of introducing a retail-facing digital tenge for second-tier banks remain uncertain. Unlike banks, private equity funds are not required to provision against each individual investment. Governments, meanwhile, have grown weary of repeatedly bailing out bank shareholders, only to see taxpayers foot the bill while the spoils are toasted in champagne.

Second, investors expect tax transparency. In practical terms, this means that investing through a fund should not result in a higher tax burden than investing directly into operating companies. This principle lies at the heart of capital pooling. Accordingly, the regulator proposes structures without legal personality – namely, unit investment funds and consortia. The critical question is whether the tax regime accompanying these structures will be at least as competitive as those offered by the AIFC and our regional peers, particularly with respect to corporate income tax, capital gains, dividend taxation, and VAT. Without a clearly articulated and competitive tax framework, investors are unlikely to make binding long-term commitments – a gap that, notably, does not appear to be addressed in the comparative materials presented to Parliament.

Third, private equity funds combine a sustainable ownership structure with long-term investments, as their strategies are typically built around five- to ten-year horizons. Early exits are therefore unlikely, since funds and portfolio companies are in the same boat.

.jpg)

Click here for a closer look at the governance specifics of private equity funds.

Background

Private equity has a history of roughly two decades in Kazakhstan. There have already been two stages during which market sought to inject capital into the economy through market-based investments in Kazakhstani enterprises.

The first such period began in the mid-1990s and lasted for approximately fourteen years. At the time, the industry was not yet referred to as private equity but rather as LBO (leveraged buyout) – arguably a more precise description, given that direct equity injections were almost always accompanied by debt leverage. Despite the absence of a dedicated regulatory framework for this segment, several investors entered the Kazakhstani market. The very reform of a mega-regulator had yet to emerge, but the National Bank had already succeeded in building what was widely regarded as the most advanced two-tier banking system in the CIS and was busy implementing International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

One such fund was established by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development under the name Kazakhstan Post-Privatization Fund with a total size of approximately EUR 30 million. The fund’s more successful investments contributed to the development of enterprises such as the Ust-Kamenogorsk Poultry Farm, the pharmaceutical company Romat, the dairy producer FoodMaster, as well as several telecommunications players, including Spectrum and Arna. Some investments failed to meet expectations for a variety of reasons. Yet this outcome is hardly unusual: the Pareto principle applies, and seasoned professionals understand that partial losses are an inevitable part of private equity investing.

Another illustrative case from Kazakhstan is Baring Vostok Private Equity III. It is a story of lenders who moved beyond earning bank interest and evolved toward a more advanced, technology-driven investment model. One of the fund’s professionals at the time was Mikhail Lomtadze. Today, thanks in part to his forward-looking vision, millions of Kazakhstanis eenjoy the results of a digital transformation through the mobile ecosystem built by Kaspi. To keep pace with Kaspi, other banks across the country were forced to adopt similar smartphone-based models. Products from legacy portfolio companies – poultry from Ust-Kamenogorsk Poultry Farm and dairy products from FoodMaster – can now be ordered via Kaspi’s mobile application. This is a tangible example of the broader social dividend generated by private equity: when capital is deployed on market terms and guided by consistent ethical standards, the spillover effects extend well beyond financial returns.

Kaspi CEO Mikhail Lomtadze

The second wave of private equity activity in Kazakhstan began in 2008 and lasted for roughly three years, under the stewardship of the then-influential economist Kairat Kelimbetov. During this period, a so-called fund of funds was established under the name Kazyna Capital Management, now operating as Qazaqstan Investment Corporation. The timing coincided with the onset of the Great Recession. Kazakhstan’s banking leaders began to lose ground due to heavy reliance on bond financing, while weaker institutions spiralled into bankruptcy. Against this backdrop, Kazyna Capital Management became one of the few domestic entities mandated to invest in funds targeting Central Asia. The experiment, however, proved short-lived. The core issue was that portfolio quality never became a central priority for policymakers and administrators. Too much faith was placed in the abstract wisdom of the “market’s invisible hand”, which in practice manifested itself as managerial opportunism aka greed. From the outset, the fund-of-funds model was not designed to focus on quality direct investments into specific Kazakhstani companies; instead, it relied heavily on foreign funds and their expertise. This approach was later reversed, when a prominent figure – albeit a hapless leader (who is now in prison for murder) – decided that expensive foreign managers were unnecessary. The result was an investment freeze lasting more than a decade – a predictable outcome in a market that ultimately operates on a quid pro quo basis.

Of course, there were many other reasons as well. One of them was the reluctance of business owners to trust the promises made by private equity funds. Incumbent owners were rarely willing to accept new partners. To them, private equity investors looked less like strategic allies and more like cynical sharks – the Edward Lewis type from the “Pretty Woman” movie. Second, employees of investment funds traditionally earn very substantial compensation, typically around two percent of assets under management – often amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars. For quasi-state managers, this income stream appeared far more tangible and attractive than transaction-based bonuses tied to deals they did not know how to execute. Hence, once again, the chronic shortage of skilled negotiators. Conducting complex negotiations is not an optional extra but a core competency in sophisticated transactions with foreign partners. And third, our state-appointed angels were once again undone by gold. Those responsible for appointing management to the newly created funds began installing loyal and grateful friends and relatives, rather than inconvenient professionals.

The fundamental distinction between the two waves lies in who deployed capital and how. During the first wave, market-driven investors targeted large enterprises from the post-Soviet real economy – companies that possessed tangible assets and industrial capacity but lacked working capital and market expertise. During the second wave, investment decisions were dominated by quasi-state managers whose experience was largely theoretical. Over time, the professional civil service has drifted further away from the entrepreneurial mindset required for risk-based capital allocation.

President Tokayev meets businessmen on 21 January 2022

The Road to Success

What would it take for the regulator’s latest attempt to attract private equity funds to succeed? Kazakhstan currently faces a shortage of capital amid yet another economic downturn. Paradoxically, this may be an advantage. As Grigory Marchenko once observed, crisis is the primary prerequisite for any meaningful reform. The key question is whether the state will once again attempt to jump-start the engine through administrative pressure, or whether it is prepared to allow genuine market participants to emerge. Will new investors be exclusively foreign, or will participation be shaped by asset-recovery policies? Will foreign investors take the form of quasi-state entities, or can one hope for the arrival of strong private operators? What advantages do Kazakhstan’s jurisdictions offer, given that the country effectively operates under two legal regimes including the Astana International Financial Centre? Governments across Central Asia and beyond are actively competing for investors, including those of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. How can familiar pitfalls and old patterns be avoided so that investment not only arrives, but remains in the economy as accumulated capital? These questions allow for non-trivial answers.

We believe that the idea of attracting private equity funds is a very good one and may well prove timely. However, the devil is in the tables. Kazakhstan today certainly represents a territory of interest for certain investors. Time does not stand still: the challenges of the past have not disappeared and have, in fact, taken on new digital forms. Life cycles have accelerated. The focal points for capital allocation are shifting from hydrocarbons to rare earth metals. It must be recognized that foreign investors pursue their own interests; yet someone must also safeguard the interests of Kazakhstan. Trust, but verify. Our market has its own professionals with experience not only in establishing private equity funds, but also in supporting their successful operation. Properly organizing difficult negotiations with foreign partners and formulating complex questions – in order to develop sound responses to them – is something that can and should be done today. After all, the best success recipe is plan plus improvisation.

Aidar Yegubayev

Managing Partner, Yegubayev & Partners